Border Violations

To understand what are border violations, we start by looking how stereoscopy creates the illusion of depth by presenting slightly different images to each eye. This creates parallax which is what makes our brain think that objects reside at different distances from the screen.

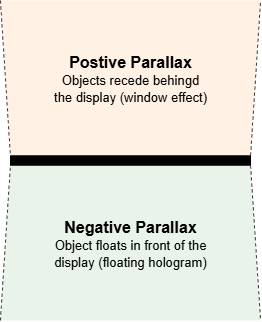

In a well-composed 3D scene, the display itself acts as close as a window. Objects with negative parallax appear to float in front of this window, while those with positive parallax recede convincingly behind it.

Displays have hard, physical borders, so when a virtual object moves toward one of these edges, it will eventually begin to disappear from view. This is where we encounter two very different scenarios:

- The Object is Behind the Window: Imagine a bird flying away past the edge of a real window. You naturally expect it to disappear from view as it passes out of sight. The same is true in stereoscopic 3D. If an object with positive parallax (behind the screen) reaches the edge, it simply vanishes. The brain accepts this effortlessly because it mirrors our everyday experience. No problem here.

- The Object is In Front of the Window: This is where the illusion breaks. Picture a bee buzzing in front of your window. As it moves to the side, you expect to see it pass over the window's frame, remaining fully visible. But in a 3D display, the virtual object can’t do that because there are no more pixels once it hits the edge and is abruptly clipped off.

Your brain is presented with an impossible contradiction: one eye receives a view where the object is complete, while the other eye sees it cut off by the screen's edge. A border violation is this conflict. It happens where a foreground object is unnaturally truncated by the very window it's supposed to be in front of. It’s a direct compromise on the illusion, pulling the viewer out of the experience and highlighting the limits of the technology.

Why Is 3D Content Prone to Border Violations?

The answer lies in a fundamental and entirely understandable creative impulse: the desire to wow an audience.

The most immediate and impressive trick in any 3D display is the "pop-out" effect. Content creators naturally want to leverage this, animating objects to leap out of the screen and often move across the field of view. This isn't a misguided or wrong choice; it's a powerful application of the technology. The same goes for a realistic human avatar. When executed well, the sensation of another person sharing your physical space is the ultimate testament to an immersive display. Ask Google and HP if you are wondering.

As it often happens, this creative goal puts objects on a direct collision course with the edges of the screen. Furthermore, common camera angles in 3D scenes almost guarantee these conflicts:

- Top-Down or Isometric Views: A staple in games and data visualization, this perspective almost invariably causes the ground plane or floor to intersect with the bottom edge of the display. This creates a permanent, glaring border violation unless carefully managed.

- Frontal Views: Whether in a narrative scene or a UI element, objects moving horizontally in a frontal view are destined to approach the left and right borders, risking violation as they exit the stage.

In a perfectly static scene, we can compose every element to avoid these edge conflicts (but remember to take into account that the user can move to the sides). Unfortunately, static content has a limited appeal. Dynamic and responsive content truly showcases the immersive potential of these displays and captivates viewers. And that's the problem, dynamic objects and exploiting depth, is also what makes it most vulnerable to this specific flaw. The challenge, then, isn't to avoid movement, but to master it.

If It's a Flaw, Why Is It So Often Ignored?

The human visual system is surprisingly forgiving to some border violations, so the key lies in understanding the conditions under which these violations become perceptually "invisible."

First, not all edges have the same impact. Most autostereoscopic displays generate disparity only in the horizontal axis, as our eyes are separated horizontally. This has a direct consequences regarding border violations:

- Top and Bottom Edges: A violation here is often handled with remarkable grace by the brain. This happens because it mimics our natural visual experience. When you look someone in the eye, their feet fall outside your central field of view without causing any perceptual crisis. The visual system readily accepts the clipping of vertical information. While I maintain it's not ideal for a perfect window-like illusion, in many practical cases, it is indeed harmless.

- Left and Right Edges: This is where the problem lies. Since horizontal disparity is the very engine of the 3D effect (and how we humans perceive depth), a violation on the sides creates a direct conflict between the data presented to each eye. The brain has no real-world precedent for an object in front of a window disappearing by the window's frame. The severity of the violation is also modulated by two factors:

- Depth Strength: An object floating far in front of the screen will produce a stark, unmissable violation. An object very close to the screen plane, however, creates only a subtle one that might escape notice.

- The "Behind the Screen" Exception: As established, objects receding behind the screen plane exit the frame naturally, just like in reality, and are never a problem.

Secondly, motion is a powerful masking agent. The brain is excellent at processing smooth continuity but can be tricked by abrupt changes.

If an object exits the frame in a single, quick motion (like literally vanishing in a frame or two tops), then the brain often lacks the time to register the visual contradiction. It's processed as the object simply leaving the field of view.

A smaller object making a quick exit (even using frew frames) is even less likely to trigger a conscious perception of error.

Finally, we must account for attention. Content is often designed to focus the viewer's gaze on the central action. Objects drifting out of the periphery are, by design, secondary. Our brains are wired to filter out peripheral anomalies in favor of processing the central point of focus. Consequently, many border violations occur unnoticed simply because the viewer isn't actively looking for them; their attention is held elsewhere.

How to Avoid Border Violations: Practical Solutions

The good news is that eliminating border violations can be quite simple. In fact, the solutions are often straightforward and can be implemented with minimal effort. The barrier is usually not feasibility, but thinking about this issues before they happen.

-

The Depth Adjustment: The Most Direct Fix If an object is about to cause a violation by exiting the frame, adjust its depth to place it behind the screen plane. This transforms a problematic "pop-out" effect into a natural "look-through-a-window" effect. The moment the object transitions behind the screen, its clipping at the edge becomes perceptually correct. This is often an elegant, foolproof solution than can preserve the dynamism of the action.

-

The Strategic Vignette: An Easy Win This is perhaps the most versatile and underutilized tool for managing edges. By applying a subtle vignette effect (a soft fade-to-black or blur along the perimeter of the screen) you create a graceful exit for any object, regardless of its depth.

A gradient of just a few pixels is enough to signal to the brain that the visual field is ending. The object doesn't abruptly vanish against a hard edge; it gradually blends into the periphery. This not only masks potential violations but also enhances the overall immersion by framing the content, much like a matte around a painting.

-

Dynamic Depth Mapping: The Advanced Way A more advanced, though technically demanding, approach is to dynamically reduce the depth range at the edges of the display. In this model, the center of the screen can enjoy full, dramatic disparity, while the periphery is gradually flattened towards the screen plane.

This technique offers a dual benefit: it preemptively neutralizes border violations and reduces crosstalk for viewers at extreme viewing angles, significantly improving the overall quality of experience. While this presents great creative potential, it is currently a content-side responsibility, as no display manufacturers that I'm aware of offer this as a native hardware feature, yet.

-

A Note on Speed: A Flawed Solution For the sake of completeness, I should mention that that animating an object to exit the frame extremely quickly can prevent the brain from registering the violation. However, I must caution against relying on this as a primary method.

Fast-moving objects in stereoscopic displays can introduce their own set of problems, from motion blur and judder to more pronounced crosstalk. Solving one artifact by introducing another potential problem is a poor trade-off.